Week 3 - AEE

| Site: | Unitec Online |

| Course: | ENGGMG7109 - Resource and Environmental Management 2022 |

| Book: | Week 3 - AEE |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 1 January 2026, 12:09 AM |

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction

- 1.1. Environmental Awareness

- 1.2. Historical Context

- 1.3. Sustainable Development

- 1.4. World's leading legislation

- 1.5. Unified Legislation

- 1.6. Effect-based approach

- 1.7. Reducing environmental impacts

- 1.8. What is an AEE ?

- 1.9. Defining Environment

- 1.10. Defining Effects

- 1.11. What is included in an AEE?

- 1.12. AEE - step by step

- 1.13. Step by step (cont.)

- 1.14. Step 4

- 1.15. Step 5

- 1.16. Step 6

- 1.17. Step 7

- 1.18. Step 8

- 1.19. Summary

1. Introduction

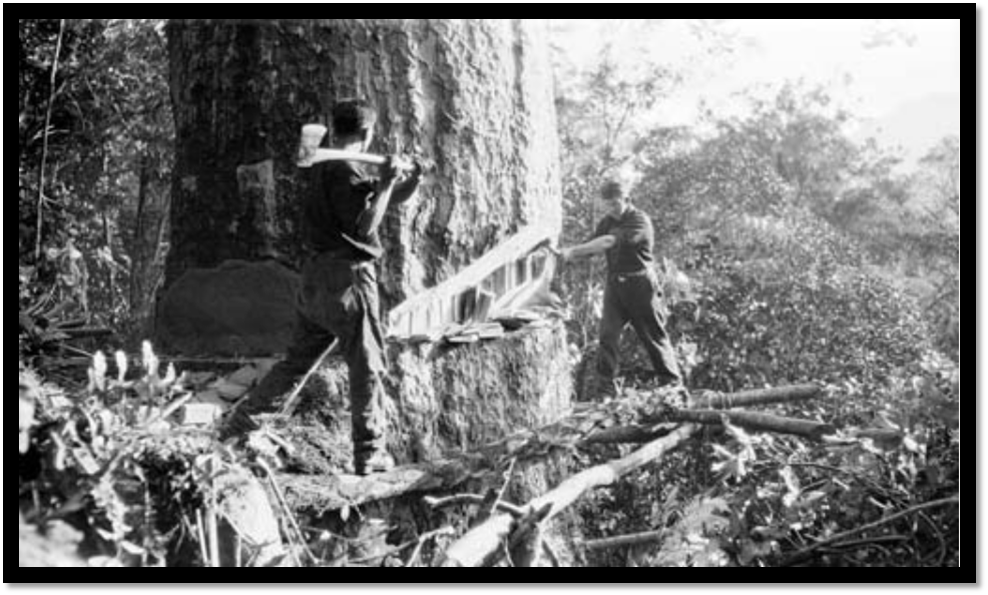

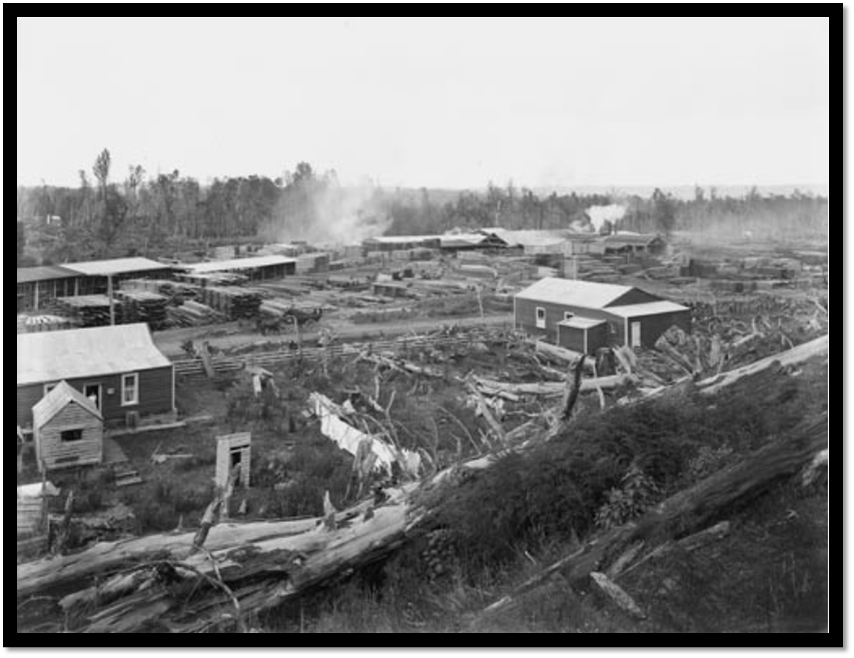

Many many years ago when the first settlers came to New Zealand, our landscape was changed forever. At that time, did they realise what they were doing to their environment ? Vast changes were made without either education or awareness of the impact of their actions.

Many many years ago when the first settlers came to New Zealand, our landscape was changed forever. At that time, did they realise what they were doing to their environment ? Vast changes were made without either education or awareness of the impact of their actions.

Over time, there was a progression from forests to roads to farms to cities and during this time, the effects of certain types of land cover on our environment were not considered (or understood). Since the adoption of the AEE process in 1991, our cities have seen a huge increase in urbanisation.

As forest was cleared for pasture, sawmills turned felled trees into timber for fuel, housing and railway sleepers. This is the Gamman & Co. sawmill, near Ohakune, around 1910.

1.1. Environmental Awareness

In more recent years, there has been a resurgence of environmental awareness in other countries, particularly developing countries such as India.

In more recent years, there has been a resurgence of environmental awareness in other countries, particularly developing countries such as India.

Debates over the effects of the impact of building development on the environment fundamentally led to the legislation we see today. In particular, in the 1950's and 1960's, vast areas of land clearing with no consideration for the environment may have started the trigger for legislation. This increasing awareness of environmental issues has led to debate at political, NGO and governmental level and has led to the creation of environmental standards.

1.2. Historical Context

The concepts underpinning the RMA were based on developments in both international and local thinking over the previous 20 years. The 1972 Stockholm United Nations Conference on Environment and Development provided the first forum for international debate on concepts such as integrated environmental management and sustainable development.

The concepts underpinning the RMA were based on developments in both international and local thinking over the previous 20 years. The 1972 Stockholm United Nations Conference on Environment and Development provided the first forum for international debate on concepts such as integrated environmental management and sustainable development.

A subsequent audit of New Zealand's environmental management by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), in 1980, highlighted the need to improve environmental management locally.

The AEE supported a trend towards better environmental management and included the consideration of people as part of this process. However, it does not include all facets of environmental management, for example, mining (which has. in part, led to the heated debates around mining on Great Barrier Island). Many activities which are not directly included in the AEE process as still impacted more indirectly by the RMA.

1.3. Sustainable Development

In 1981, the Nature Conservation Council prepared a report titled Integrating Conservation and Development: A Proposal for a New Zealand Conservation Strategy. This was one of the first documents to identify how the key ideas underlying the concept of sustainable development could be applied in New Zealand.

In 1981, the Nature Conservation Council prepared a report titled Integrating Conservation and Development: A Proposal for a New Zealand Conservation Strategy. This was one of the first documents to identify how the key ideas underlying the concept of sustainable development could be applied in New Zealand.

During the early 1980s, there was a growing appreciation that key environmental legislation, including the Water and Soil Conservation Act 1967 and the Town and Country Planning Act 1977, needed to be reviewed.

Later that decade, the new Labour Government began to investigate and implement institutional reform for environmental management at both the national and local government levels.

1.4. World's leading legislation

Work began on formally reviewing a number of environmental statutes in July 1988, after the Labour Government was re-elected to power. In December 1988, the government issued a proposal for a single integrated resource management statute that would replace the many existing statutory procedures.

Work began on formally reviewing a number of environmental statutes in July 1988, after the Labour Government was re-elected to power. In December 1988, the government issued a proposal for a single integrated resource management statute that would replace the many existing statutory procedures.

After an extensive consultation process, the Resource Management Bill was introduced into Parliament in December 1989, but the Labour Government lost power in 1990 before it was passed into law.

The new National Government decided to continue with the Bill, but first gave it to a Review Group for further consideration. As a result of the review, the minerals section was dropped from the Bill (and enacted separately as the Crown Minerals Act 1991) and other changes made. A revised Act was passed by Parliament in August 1991.

At the time of its creation, the AEE process was considered to be one of the leading pieces of environmental legislation in the World. This is partly due to the effect-based approach of this legislation. This approach allowed certain activities to continue but sort to separate incompatible activities, however for this to work effectively, understanding effects meant understanding the environment.

1.5. Unified Legislation

When enacted, the RMA repealed 78 statutes and regulations, and amended numerous others, to provide a single piece of legislation for the management of land, water, soil and air throughout New Zealand. The Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996 subsequently replaced the hazardous substances section of the RMA, which never came into force.

When enacted, the RMA repealed 78 statutes and regulations, and amended numerous others, to provide a single piece of legislation for the management of land, water, soil and air throughout New Zealand. The Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996 subsequently replaced the hazardous substances section of the RMA, which never came into force.

Some significant resource management activities are outside the jurisdiction of the RMA, or have overlapping management regimes.

These include the harvesting of fish, shellfish and seaweed stocks which are managed under the Fisheries Act 1996, the logging of indigenous forests on private land which are also managed under the Forests Act 1949 and marine pollution from ships and offshore structures which is also managed under the Maritime Transport Act 1994. The RMA does not, therefore, provide a fully integrated resource management regime. As an example, the development of Auckland had no strategic planning in terms of environmental constraints when building new communities - it was more a case of who was willing to sell land at that time rather than a structured design. (image www.ontario.sierraclub.ca)

These include the harvesting of fish, shellfish and seaweed stocks which are managed under the Fisheries Act 1996, the logging of indigenous forests on private land which are also managed under the Forests Act 1949 and marine pollution from ships and offshore structures which is also managed under the Maritime Transport Act 1994. The RMA does not, therefore, provide a fully integrated resource management regime. As an example, the development of Auckland had no strategic planning in terms of environmental constraints when building new communities - it was more a case of who was willing to sell land at that time rather than a structured design. (image www.ontario.sierraclub.ca)

1.6. Effect-based approach

The RMA's approach to environmental management is firmly rooted in the concepts of sustainable management and the integrated management of resources. Other approaches adopted included 'effects-based' assessments, principle- and policy-based environmental management and subsidiarity. The first step involves confirming need for legislation or restrictions and then imposed restrictions on certain activities may shape proposal with an aim to reduce effects (image www.bbc.co.uk)

The RMA's approach to environmental management is firmly rooted in the concepts of sustainable management and the integrated management of resources. Other approaches adopted included 'effects-based' assessments, principle- and policy-based environmental management and subsidiarity. The first step involves confirming need for legislation or restrictions and then imposed restrictions on certain activities may shape proposal with an aim to reduce effects (image www.bbc.co.uk)

The RMA focuses on managing the effects of activities rather than regulating the activities themselves. This heralded a move away from a more prescriptive planning approach under the Town and Country Planning Act 1977. That Act sought to guide the location of activities and to separate incompatible activities.

Identifying the status of an activity can be achieved at an early stage by conversation with local authorities or by accessing the website. This link will take you a very helpful website concerned with activity status - LINK

Activities may be defined as:

- Permitted (no consent required)

- Controlled (consent required and conditions may be applied, e.g set hours of operation)

- Restricted Discretionary (may be approved or declined due to adverse effects in specific areas e.g amenity values or noise)

- Discretionary (may be approved or declined for any (non-specific) reason)

- Non-complying (may be approved or declined - must prove that any adverse effects are less than minor)

- Prohibited - e.g no subdivisions are allowed in the Waitakere ranges or no nuclear power in NZ

1.7. Reducing environmental impacts

The RMA adopts a more enabling approach which seeks only to intervene where activities are likely to result in unacceptable environmental impacts.

The RMA adopts a more enabling approach which seeks only to intervene where activities are likely to result in unacceptable environmental impacts.

This approach has the advantage of focusing on the reduction of environmental impacts. It can also, however, result in environmental planning being reactive rather than proactive, in plans being complex and difficult to understand, and in poor management of cumulative and diffuse impacts (image www.fmcgnews.co.uk)

1.8. What is an AEE ?

An AEE should be seen as part of the process of shaping your proposal, or what you want to do, rather than a task to do once you have all your plans prepared. An AEE helps you identify the effects of your activity early on in the process and, if necessary, allows you to incorporate measures to reduce any adverse effects. Steps include confirming with Council what consents are required. Once established, an assessment of environmental effects (AEE) is required to get a decision from the council on whether you can do what you want to do. It identifies who you should consult and, if required, from whom you should obtain written approval. It is used as the basis for the council’s decision on whether to notify and grant an application, and, if granted, whether to impose any conditions to address any outstanding effects (Figure: www.mfe.govt.nz)

An AEE should be seen as part of the process of shaping your proposal, or what you want to do, rather than a task to do once you have all your plans prepared. An AEE helps you identify the effects of your activity early on in the process and, if necessary, allows you to incorporate measures to reduce any adverse effects. Steps include confirming with Council what consents are required. Once established, an assessment of environmental effects (AEE) is required to get a decision from the council on whether you can do what you want to do. It identifies who you should consult and, if required, from whom you should obtain written approval. It is used as the basis for the council’s decision on whether to notify and grant an application, and, if granted, whether to impose any conditions to address any outstanding effects (Figure: www.mfe.govt.nz)1.9. Defining Environment

How the RMA defines the environment is very important, the environment includes-

How the RMA defines the environment is very important, the environment includes-

(a) Ecosystems and their constituent parts, including people and communities; and

(b) All natural and physical resources; and

(c) Amenity values; and

(d) The social, economic, aesthetic, and cultural conditions which affect the matters stated in paragraphs (a) to (c) of this definition or which are affected by those matters.

1.10. Defining Effects

Effect includes-

Effect includes-

(a) Any positive or adverse effect; and

(b) Any temporary or permanent effect; and

(c) Any past, present, or future effect; and

(d) Any cumulative effect which arises over time or in combination with other effects (e.g noise, dust)

regardless of the scale, intensity, duration, or frequency of the effect, and also includes—

(e) Any potential effect of high probability; and

(f) Any potential effect of low probability which has a high potential impact (e.g dam spill or 10-year storm) (image www.eofdreams.com)

Positive effects may influence whether or not a consent is granted and adverse effects can affect the decision for notification. Temporary effects are often identified during construction and cumulative effects may include affects on air quality from transportation development. If an activity only affects a few people then it is worth obtaining agreement from all parties prior to work commencing to avoid notification.

1.11. What is included in an AEE?

Your AEE should include the following (unless the council’s plan states otherwise), as set out in section 88 and the Fourth Schedule of the RMA:

Your AEE should include the following (unless the council’s plan states otherwise), as set out in section 88 and the Fourth Schedule of the RMA:

1. A description of your proposed activity.

2. An assessment of the actual and potential effects on the environment of your activity.

3. Where the above effects are likely to be significant, a description of available alternatives.

4. A discussion of the risk to the environment from hazardous substances and installations.

5. For contaminants, an assessment of the nature of the discharge and sensitivity of the receiving environment to the adverse effects and any possible alternative methods of discharge, including discharge into any other receiving environment.

6. A description of how the adverse effects may be avoided, remedied or mitigated.

7. Identification of the persons affected by the proposal, the consultation undertaken, if any, and any response to the views of any person consulted.

8. Where an effect needs to be controlled, a discussion of how it can be controlled and whether it needs to be monitored. Where appropriate, a description of how this will be done and by whom.

While an AEE is mandatory, the Fourth Schedule should be used as a guide rather than a blueprint for its preparation. The council’s plan is also likely to list the information you need to supply. (image courtesy of www.ila-chateau.com).

Follow this link to find the MfE's free guide to preparing an AEE →

1.12. AEE - step by step

Step 1: Identify the activities for which a resource consent is sought.

Step 1: Identify the activities for which a resource consent is sought.

Fully understanding the environmental effects of an activity is essential for the proper preparation of an Assessment of Environmental Effects (AEE). You will need to think about your proposal and how it will change the site you intend to use/develop.

Step 2: Conduct a Site Inspection

What does it look like ?

- Natural features

- Adjacent uses

- Physical features

For example:

- Is the site flat or sloping?

- Are there any significant trees or vegetation?

- Are there any unusual features?

- What is on the neighbouring properties?

- Is there access to Council services?

- Archaeological sites ?

1.13. Step by step (cont.)

Step 3: Talk to staff at the Council.

Step 3: Talk to staff at the Council.

Once you have done your homework it is a good idea to talk to someone at the Council. The Council is likely to have pamphlets, checklists and forms to help you prepare an AEE.

If you don't know how to use a regional/district plan, ask the Council staff to help you. A word of warning: some councils charge for information and time spent helping you.

To summarise this step : communication is very important - talk to council staff as they are responsible for proposing consents so verbal communication from them is important. This ensures that you are ahead of their expectations and are well informed should these expectations change. Understand their charging regime is also useful as meetings may incur charges which have not been planned for.

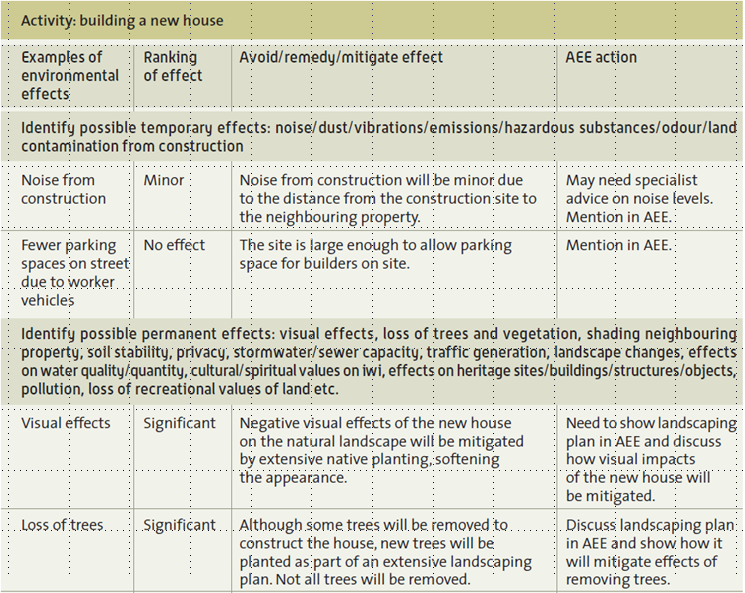

Step 4: Identify the environmental effects

Understand the environmental issues arising from your proposal. An environmental effect is any change to the environment created by an activity. This includes effects on ecosystems, natural resources (land, air and water), buildings and people.

- positive or negative

- temporary or permanent

- past, present or future

- cumulative (occur over time or in combination - with other effects)

- of high probability

- of low probability but high impact.

Chicago city hall green roof - a positive effect! (Image courtesy of www.organicconnectmag.com)

1.14. Step 4

Checklist

Checklist

- degradation of historic or cultural sites

- vegetation loss (what type and how much?)

- decreases in water quality/quantity

- loss of privacy (noise expert required ?)

- odour (odour control? properly maintained?)

- visual impact (landscape architect rep. may be required), also there are requirements in district plan to not block light

- changes to coastal processes (impact on benthos? impacts further along coast?)

- discharge of contaminants into air/water

- use of hazardous substances

- loss of recreational values.

AEEs should anticipate the unexpected. You need to look for specific environmental effects arising from your proposal in combination with the site and its locality. Once you have identified the actual and potential effects, you should consider how significant they are likely to be. Emotional politics are important so good news stories have a role. Also make sure that you keep everything clear and structured for those checking at council.

You should also use the above list to help you consider the nature of the effects as well as their scale, intensity, duration and frequency.

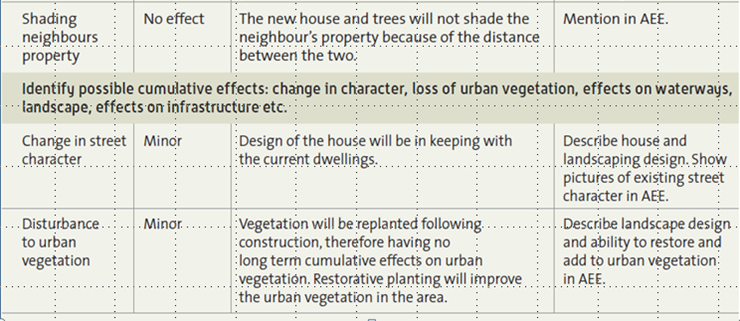

For example, an extension to an existing building may result in the following effects:

- temporary effects (while the extension is being built) - dust, noise and fewer parking spaces

- permanent effects - loss of privacy, shading, visual effects and the loss of significant trees

- cumulative effects - change in street character and loss of urban vegetation.

1.15. Step 5

Step 5: How do I rank the effects?

Step 5: How do I rank the effects?

- the effect can be avoided?

- the effect can be mitigated?

- the effect can be remedied?

"more than minor" is a key RMA statement which supports the avoiding as being the best option. Be mindful of wording for effects as significant effects will suggest a higher level mitigation and probably notification. Also remember to assess effects which occur downstream of the activity, for example a supermarket in a suburban area may need traffic lights for entry and exit - how will these effects other parts of the transportation route around the supermarket ??

1.16. Step 6

Step 6: Pre- application meeting (Complex)

Step 6: Pre- application meeting (Complex)

Pre- application meeting with council for some feedback is very useful. Talking in advance often results in a better outcome. There may be more than one meeting with more than one client. It is important to keep questions on track and avoid railroading in these meetings. Be prepared to stick to the purpose of a meeting.

There are regional variations in the approach of the councils and variations between one council officIal and another official from the same office. Ensure that you record the minutes as this controls the situation better. Check that any minutes taken by external parties are true and accurate to avoid problems later. Ensure that you finalise the best and the cheapest way and re-evaluate your proposal. Make an effort to resolve any restrictions before submitting your consent. Alternatives options often cost money and make the process more complicated. Document all alternatives in case you are asked for proof that you have looked at other options at a later date. Finally make sure that your monitoring proposal is both feasible and affordable - do not promise what cannot be delivered.

In summary:

When is the application complex ?

- Something unusual about the site

- Issue pre-existing

- Technical details complex

- Agree on information to provide

- Techniques or methods to be used. Remember that methods of monitoring may be required which can be tricky, time consuming or expensive.

What's the procedure for the meeting ?

- Depends on Council but usually recorded in minutes and Council may charge.

1.17. Step 7

Step 7: Re-evaluate your proposal

Step 7: Re-evaluate your proposal

Use the AEE process to help design your proposal.

You may decide that some environmental effects will be significant and that you need to change your proposal to avoid, remedy or mitigate them. One difficulty is how to determine significance ? E.g are we affecting the Maui dolphin in Auckland's harbour ?

You should then think about alternative ways to achieve the same goals while considering the environmental effects each alternative may have. This process can result in a “win-win” situation, with better proposal design and better environmental outcomes.

“Avoid”, “remedy” and “mitigate” are terms used in the Resource Management Act. Each represents a different way of addressing an adverse effect so that it is acceptable.

1.18. Step 8

Step 8: Finalise the AEE

Step 8: Finalise the AEE

Check you have all the information to draft your AEE. This means you have all the information to:

- accurately describe the activity

- accurately describe the site and locality

- complete your effects checklist, including ranking and discussing how any adverse effects may be avoided, remedied or mitigated

- identify any consultation undertaken and its results

- clearly identify any restrictions on the consent where these have been imposed to resolve affected parties’ concerns (where significant effects are likely to occur) identify alternatives you have considered and why they were rejected

- identify any proposals for monitoring potential and actual effects.

1.19. Summary

Remember

You need to include enough information in your AEE so that the Council can evaluate your proposal. The amount of information should correspond to the scale and significance of the environmental effects that may be generated by your proposal.

- An AEE needs to include:

- A full description of the proposal, including the site and locality (including a site plan and plans of your proposal)

- A description of the environmental effects, including the significance and nature of the effects (address specific environmental effects that you have identified as well as referring to issues identified in the district and/or regional plan)

- A description of alternatives to avoid, remedy or mitigate any significant environmental effects

-

An assessment of any risks to the environment that may arise from hazardous substances and/or the discharge of contaminants.

-

A record of any consultation, including names and views of people you talked with.

A discussion of any effects that may need to be controlled or monitored, how the control or monitoring will be carried out and by whom.

References