Week 6 - People

| Site: | Unitec Online |

| Cours: | ENGGMG7109 - Resource and Environmental Management 2022 |

| Livre: | Week 6 - People |

| Imprimé par: | Visiteur anonyme |

| Date: | lundi 5 janvier 2026, 23:04 |

1. People

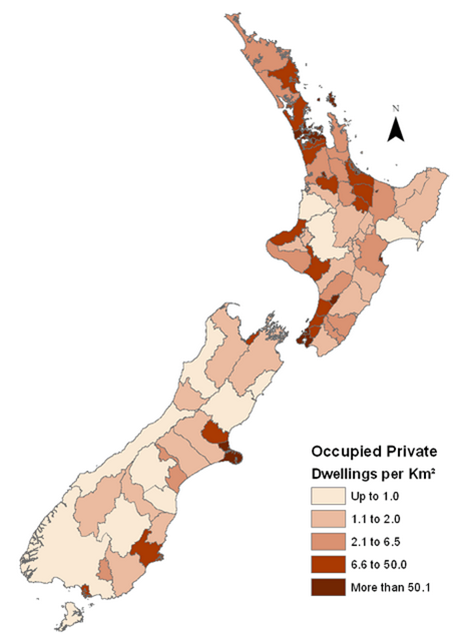

There are 4.8 million people living in New Zealand. The majority of New Zealand's population is of European descent (69% identify as "New Zealand European"), with the indigenous Māori being the largest minority (14.6%), followed by Asians (9.2%) and non-Māori Pacific Islanders (6.9%). Over three-quarters of New Zealand's population live in the North Island (76%) with one-third of the total population living in the Auckland region. This region is also the fastest growing, accounting for 46% of New Zealand's total population growth. Most Māori live in the North Island (87%), although less than 25% live in Auckland.

There are 4.8 million people living in New Zealand. The majority of New Zealand's population is of European descent (69% identify as "New Zealand European"), with the indigenous Māori being the largest minority (14.6%), followed by Asians (9.2%) and non-Māori Pacific Islanders (6.9%). Over three-quarters of New Zealand's population live in the North Island (76%) with one-third of the total population living in the Auckland region. This region is also the fastest growing, accounting for 46% of New Zealand's total population growth. Most Māori live in the North Island (87%), although less than 25% live in Auckland.

New Zealand is a predominantly urban country, with 86% of the population living in an urban area. About 72% of the population live in the 16 main urban areas (population of 30,000 or more) and 53% live in the four largest cities of Auckland, Christchurch, Wellington, and Hamilton. a quarter (24%) live in Auckland.

1.1. Environmental Effects

Under the legislation, environmental effects cover a huge range of activities including:

Under the legislation, environmental effects cover a huge range of activities including:

- Noise and vibration.

- Discharge to air, water and environment.

- Emission of contaminants.

- Odours.

- Visual effects particularly where they are negative.

- Overshadowing other properties.

- Increased traffic flow.

- Reduction of privacy.

When roads and transportation routes are built, the following affects on people may be observed:

- Separation of communities from new roads through the physical barrier they represent

- Change of nature of the aesthetic environment – landscape impacts

- Increases in pedestrian or road traffic resulting in safety effects including stranger danger

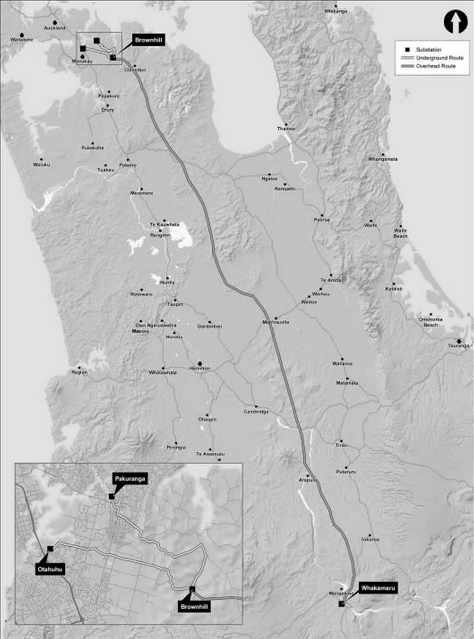

When the proposal for the new 400kV transmission line was submitted, public opinion played a role in the eventual rejection of the proposal. A letter from Catherine Tuck (Chairperson of the Whitford residents and ratepayers association) was taken into account.

1.2. Mauri-o-meter

If you are carrying out an activity which you think will have an impact on local Iwi then you can use the mauri-o-meter (designed by University of Auckland) as a good starting point - link

Don't forget that the use of this tool does not mean that you do not need to collaborate !

2. Assessment tools

Assessment tools, considerations or processes that may be used:

Assessment tools, considerations or processes that may be used:

- CPTED

- Social Impact Assessments

- Historic Places

- Landscape Assessment

- Consultation

2.1. CPTED

CPTED

Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED- pronounced Sep-Ted) is a crime prevention strategy which outlines how physical environments can be designed in order to lessen the opportunity for crime. This is achieved by creating environmental and social conditions that:

- maximise risk to offenders (increasing the likelihood of detection, challenge and apprehension)

- maximise the effort required to commit crime (increasing the time, energy and resources required to commit crime)

- minimise the actual and perceived benefits of crime (removing, minimising or concealing crime attractors and rewards)

- minimise

excuse making opportunities (removing conditions that encourage/facilitate

rationalisation of inappropriate behaviour).

The CPTED guidelines considers design and use, identifies which aspects of the physical environment affect the behaviour of people and then uses these factors to allow for the most productive use of space while reducing the opportunity of crime. This might include changes to poor environmental design such as street lighting and landscaping. CPTED concepts and principles are ideally incorporated at the design stage of a development, but can also be applied to existing developments and areas where crime and safety are a concern.

3. Social Impacts

Social Impact Assessment (SIA)

A Brief History of SIA

The legal basis of SIA (and increasing public awareness) first emerged in 1969/1970 when the US National Environment Policy Act (NEPA) introduced a requirement to ensure that major federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment should be assessed for the likely impact of such actions (see Burdge and Vanclay, 1995).

The inquiry into the proposed Mackenzie Valley gas pipeline from Yukon Territory to Alberta, Canada (1974-1978) was the first major Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) case that was overturned for social reasons. The proposed project was rejected due to a failure to consider the impacts on the local tribes.

Since then, SIA has been progressively introduced to many countries around the world.

What is SIA?

The International Principles for Social Impact Assessment defines SIA as “the processes of analysing, monitoring and managing the intended and unintended social consequences, both positive and negative, of planned interventions (policies, programs, plans, projects) and any social change processes invoked by those interventions”.

Simply put, SIA is the process of identifying and managing the social issues of project development. This process includes the effective engagement of affected communities in participatory processes of identification, assessment and management of social impacts.

3.1. Why Conduct an SIA

Why do we need to conduct a SIA?

The following are some of the reasons for conducting a SIA:

- SIA has the potential to identify local knowledge that could guide project siting decisions and reduce cost to companies that comes from poor siting decisions.

- Better decisions can be made about which interventions should proceed and how they should proceed.

- Mitigation measures can be implemented to minimise the harm and maximise the benefits from a specific planned intervention or related activity.

- Reduces likely future costs in the form of litigation, delays to approval, managing protest actions or addressing violence against staff and/or property.

- Enables a more sustainable and equitable biophysical and human environment.

The SIA process can begin with a preliminary SIA which is usually done prior to a full SIA. A preliminary SIA involves a desk-based research approach to gathering relevant data and information on project area, demographics, history, etc.

3.2. Examples of Social Impact

Social impacts are changes to one or more of the following:

- Culture – that is, shared beliefs, customs, values and language or dialect.

- Fears and aspirations – perceptions about safety, fears about the future of the community, and aspirations for the future and the future of the children.

- Personal and property rights – particularly whether people are economically affected, or experience personal disadvantage which may include a violation of their civil liberties.

- health and wellbeing – health is a state of complete physical, mental, social and spiritual wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

- Environment – the quality of the air and water people use, the availability and quality of the food they eat, the level of hazard or risk, dust and noise they are exposed to, the adequacy of sanitation, their physical safety, and their access to and control over resources.

- Community and way of life – the community’s cohesion, stability, character, services and facilities, how they live, work, play and interact with one another on a day-to-day basis.

- Political systems – the extent to which people are able to participate in decisions that affect their lives.

3.3. SMA in RMA

SMA in RMA

Consideration of social effects is required in addressing the fourth schedule of the RMA 1991 (assessment of effects on the environment). Within the RMA, effects that must be addressed when preparing an assessment of effects on the environment include:

- any effect on those in the neighbourhood and, where relevant, the wider community including any socioeconomic and cultural effects;

- any physical effect on the locality, including any landscape and visual effects;

- any effect on natural and physical resources having aesthetic, recreational, scientific, historical, spiritual, or cultural, or other special value for present or future generations.

Note that the Resource Management Act 1991 will be repealed and replaced with new laws.

The three new Acts will be the:

- Natural and Built Environments Act (NBA) to provide for land use and environmental regulation (this would be the primary replacement for the RMA).

- Strategic Planning Act (SPA) to integrate with other legislation relevant to development, and require long-term regional spatial strategies.

- Climate Change Adaptation Act (CAA) to address complex issues associated with managed retreat and funding and financing adaptation.

It is expected that the complete NBA and the SPA will be formally introduced into Parliament by the end of 2021, with the NBA passed by the end of 2022.

3.4. Activities within an SIA

Some activities within an SIA

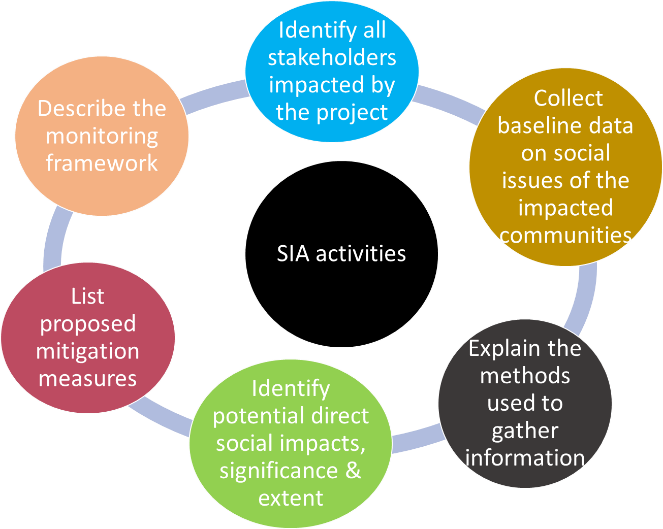

The activities when conducting an SIA include, but is not limited to the following:

- Identify stakeholders, groups and communities impacted by the project.

- Collect baseline data covering key social issues of the impacted communities such as community history, indigenous communities, culture and key events that have shaped economic and social development, current and previous key industries within the community.

- Explain the methods used to gather information, including a description of how the communities of interest were engaged during the development of the SIA.

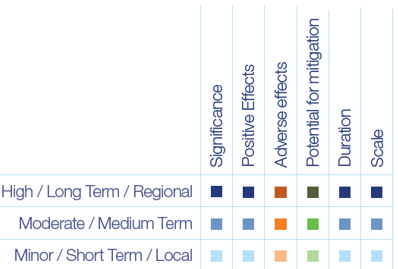

- Identify potential direct social impacts and prediction of the significance, duration and extent of any impacts.

- List proposed mitigation measures.

- Describe the monitoring framework that informs stakeholders on the progress of the project.

It is important to note that social impacts start long before project approval is required – they start with rumours of a possible project. Managing the social issues (and thus SIA), therefore, needs to start as soon as possible – after projects are conceived.

3.5. Applications of SIA

Applications of SIA in project cycles

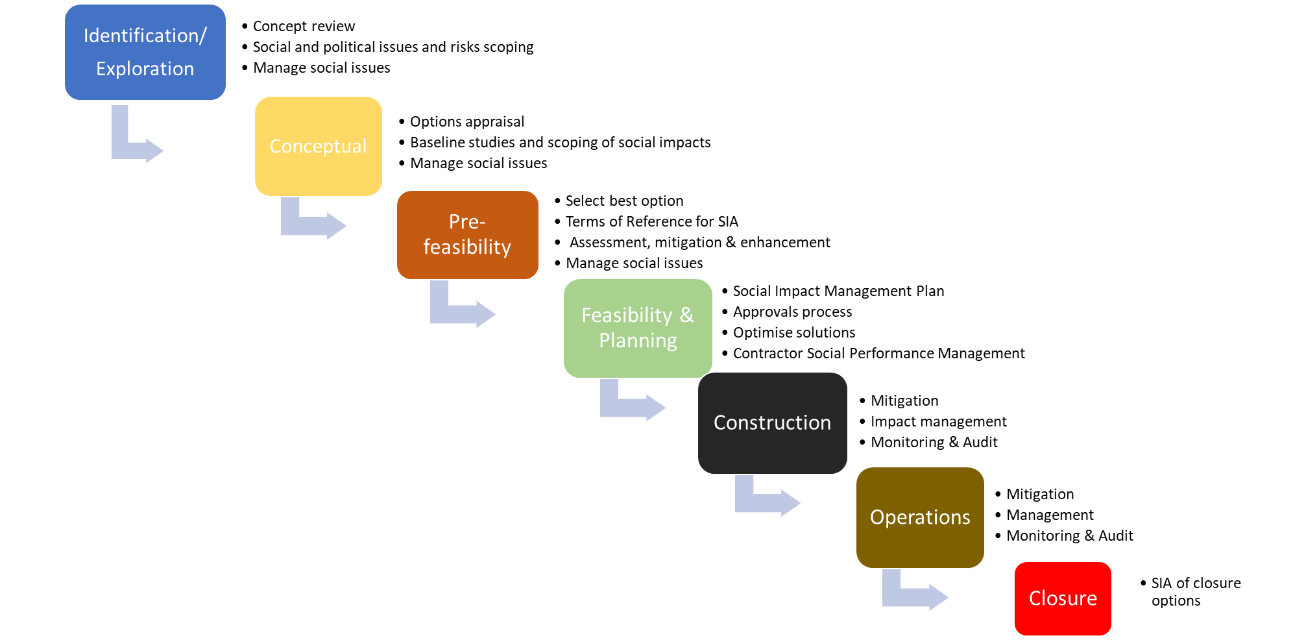

SIA plays a potential role in a typical project cycle and thus, can be applied in all phases of the project cycle. While the project cycle is usually depicted as a linear process, the reality is not so straight forward. Projects do not necessarily transition smoothly from phase to phase, and may become stalled at a certain phase, or may be sent back to earlier stage. Thus, the SIA needs to be responsive and quickly adapt to the changing needs of a project.

The diagram shows the role of SIA in each phase of a typical project cycle.

Source: Vanclay, F. et al. (2015). Social Impact Assessment: Guidance for assessing and managing the social impacts of projects.

3.6. The phases of SIA

The phases and tasks of SIA

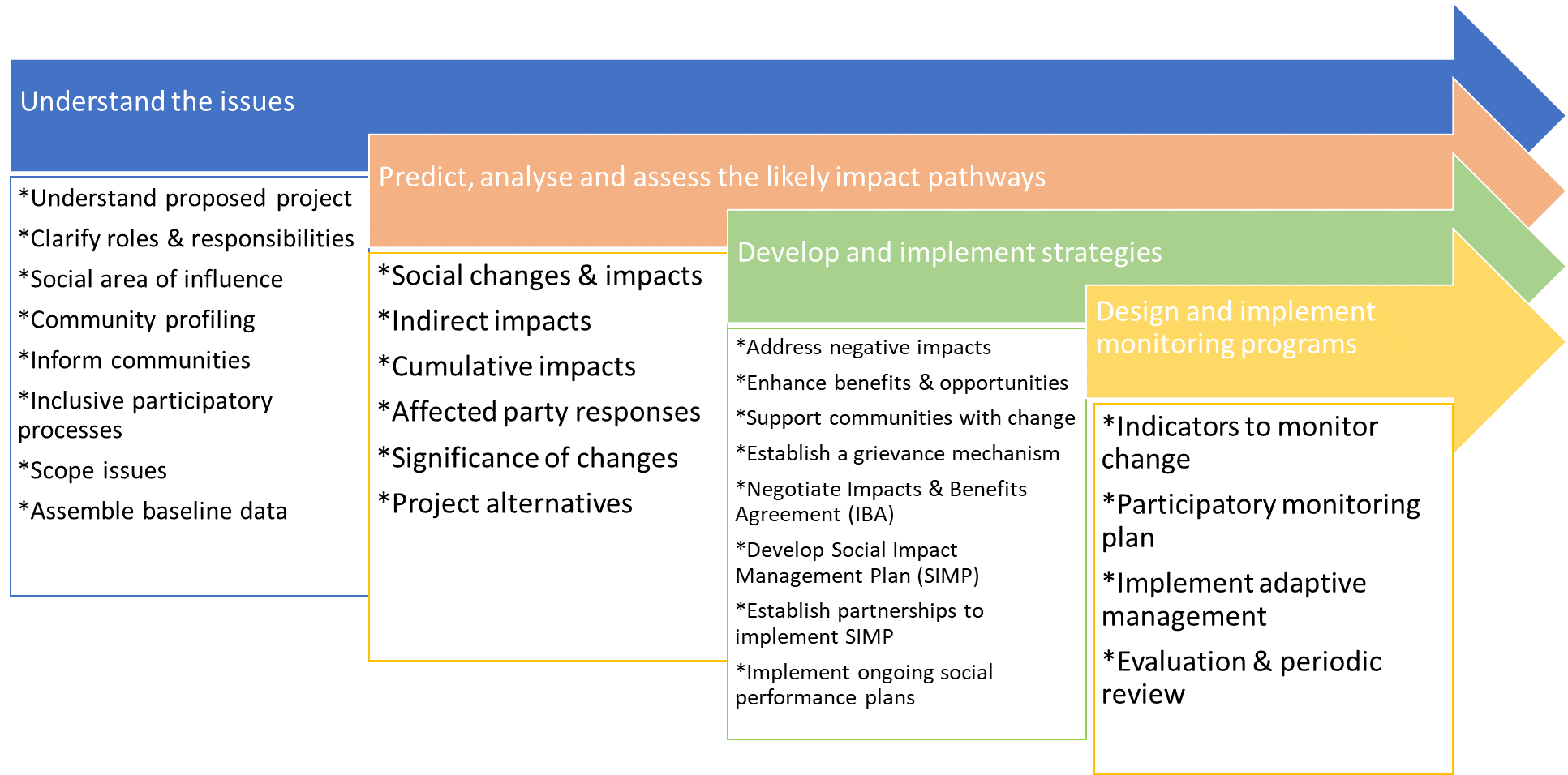

The International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA) (one of the leading associations within the SIA field) has categorised the phases and tasks within SIA as follows:

Phase 1: Understand the issues

Phase 2: Predict, analyse and assess the likely impact pathways

Phase 3: Develop and implement strategies

Phase 4: Design and implement monitoring programs

Source: Vanclay, F. et al. (2015). Social Impact Assessment: Guidance for assessing and managing the social impacts of projects.

3.7. Preparation for SIA

Preparing for SIA

During the SIA process, usually, there will be requirements for specific reports and plans at different times, particularly as inputs to project approval.

It is important to understand that the SIA is a process rather than a product or document. However, there are guiding documents and reports that will provide direction throughout the process. These documents include:

1) A Social Impact Management Plan

A Social Impact Management Plan includes details of:

(a) the measures to be taken during the implementation and operation of project activities to eliminate adverse social impacts, or to reduce them to acceptable levels, and

(b) the actions needed to implement these measures.

In summary, in case of a social impact, what will you do? How will you do it? Who will do it?

2) Community Health & Safety Plan

The Community Health and Safety Standard recognizes that project activities, equipment, and infrastructure can increase community exposure to risks and impacts. Potential negative impacts affecting health and safety may arise from a broad range of supported activities, including from infrastructure development and construction activities, changes in the nature and volume of traffic and transportation, water and sanitation issues, use and management of hazardous materials and chemicals, impacts on natural resources and ecosystems, the influx of project labour, and potential abuses by security personnel.

The Community & Health Safety Plan addresses the need and how to avoid or minimize the risks and impacts to community health, safety and security that may arise from project-related activities, with particular attention given to disadvantaged and marginalized groups.

3) Resettlement Action Plan

Resettlement Action Plan includes the need to provide resettlement, compensation, and / or livelihood restoration assistance to persons that are currently utilising project affected land.

- Survey administration, initial scoping and early resettlement planning

- Formulation of compensation

- Development of a framework for benefits and asset valuation

- Community consultation

- Identification of resettlement and livelihood restoration measures

- Preparation of resettlement database

- Development of grievance redress mechanisms

- Development of a monitoring and evaluation framework

- Preparation of an implementation plan

4) Stakeholder Engagement Plan

The stakeholder engagement plan allows the project manager to devise a systematic approach to ensure expectations, decisions, risk/issues and project progress information is delivered to the right person at the right time with the most efficient level of information. The engagement of stakeholders is not something that happens towards the end of the SIA procedure; it needs to be part of the whole process from onset to conclusion.

Your plan should include, but is not limited to:

- Defining target groups

- Specifying objectives

- Determining your main messages

- Selecting appropriate tools for communication

- Identifying spokespersons

- Monitoring and reviewing action steps.

These documents collectively provide an integrated set of actions and procedures to manage the social issues created by the project.

3.8. Ruataniwha Plains Water Storage Scheme

A case study of SIA

The project: Ruataniwha Plains Water Storage Scheme, Central Hawke’s Bay.

Project background: In 2012, there was a proposal for a deal between the Department of Conservation and Hawke's Bay Regional Council to acquire part of the protected Ruahine Forest Park so it could be flooded for the $900 million water storage and irrigation project. The scheme would dam 22ha of formerly-protected land and give the Department of Conservation 170ha of nearby farmland in return.

As part of the investigations for water storage, irrigation and intensified land uses, the Council has consulted with farmers and key stakeholders and established the Ruataniwha Stakeholder Group (RSG). The RSG represents a wide range of interests with members including the respective councils, Maori, land owners and water users, recreation, conservation and environmental interests.

Potential social effects/impacts:

- Changes in farming practices

- Changes in land ownership

- Demographic changes (numbers and composition of the population)

- Strengthening rural communities (education, health, commerce, clubs etc)

- Value conflicts associated with new / intensified land uses versus traditional dryland farming practices

- Wider regional socio-economic effects including construction effects.

Initiatives for managing impacts:

- Develop a coordinated employment strategy with agencies and training providers for future land uses and off-farm opportunities including training and skills development, with an emphasis on local placement, including working closely with Maori.

- Build on community, youth and sports and recreation development in the district to enhance community benefits from incoming population.

- Establish a programme to assist the integration of newcomers into the community, including migrants from outside the district and overseas workers.

- Develop a strategy to encourage to identify and retain important landscape values in the face of land-use change.

The problem: Forest & Bird challenged the deal

The outcome: The Supreme court ruled against the project. The reason given was that the Conservation Act allowed the responsible Minister to revoke protected status "only where its intrinsic conservation values no longer warrant such protection".

What the ruling meant was that protected conservation land across the country could not be sold or swapped for commercial ventures.

3.9. Activities

Class activities

Scenario 1

A dam is to be built across a village in the mountain. What are the likely impacts?

Consider the following: resident livestock herders, caves used for shelter, alternative grazing on valley floors when they could not go to the mountains, presence of traditional healers, neighbouring villages.

Scenario 2

Imagine you are a parent with children, living in a neighbourhood with access to park facilities. Then you receive a letter in the mailbox saying that the new park will now be used for housing development. You are then encouraged to use the next closest park, which is 20 minutes ride by car. How would you react? What would you be losing? What would you be gaining?

4. Historic Places & Cultural Heritage

Historic Places

Historic Places

Historic heritage places may have significant aesthetic, archaeological, architectural, cultural, historical, scientific, social, spiritual, technological or traditional value, and be appreciated by the public for their contribution to New Zealand’s heritage environment.

Historic heritage describes the range of place-based heritage. It is defined in the RMA (s2) and includes:

- historic buildings and structures

- archaeological sites

- places of significance to Māori including waahi tapu (sacred places) – these may include: natural features such as trees, springs, rivers or mountains which were associated with historical or cultural activities or events but which have no known physical remains of those activities or events and also includes the surroundings of buildings, sites and places.

When do you need to address cultural heritage?

The following are examples of instances when your activity may affect cultural heritage. If any of the following apply to your activity or development area, you will need to address cultural heritage in your resource consent application.

- If your activity affects a Registered or scheduled historic place, historic area, wähi tapu or wähi tapu area.

- If your activity affects an archaeological site.

- If your activity affects a place of significance to tängata whenua.

- If your development area has been occupied by people for more than 100 years.

- If your development area is located within 2km of the coast.

- If your consent involves any earthworks or ground disturbance.

- If you are applying for a consent to subdivide your property.

How can you help to identify a cultural heritage site or area?

- The New Zealand Historic Places Trust (NZHPT) - for the Register of historic places, historic areas, wähi tapu and wähi tapu areas.

- The AUC - for the Regional Plan: Coastal 2004 schedules of protected and preserved historic and cultural heritage sites.

- District and city councils (territorial authorities) – for Plan schedules of protected cultural heritage resources, related rules and provisions, and whether you require any additional consents.

- Iwi agencies - for taonga and wähi tapu.

- The New Zealand Archaeological Association -for archaeological sites in the Site Record File.

- Other agencies and sources of information include local museums, historical societies and heritage protection authorities (under the RMA).

4.1. Landscape Assessment & Consultation

Two important assessment tools for determining the impact of an activity on people are Landscape Assessment and Consultation.

Landscape Assessment

Factors that can help in identifying valued landscapes include:

- Presence/absence of statutory landscape designations;

- Presence/absence of local landscape designations and associated controls;

- Landscape quality/condition;

- Scenic quality;

- Rarity of particular elements/features;

- Representiveness;

- Conservation interest;

- Recreation value;

- Perpetual aspects; and

- Cultural / iwi.

First image (junction at highway 16 Auckland from www.loveyourneighbour.co.nz

Consultation

Consultation

In terms of consultation, in the context of seeking a resource consent, consultation is the process of communicating with people or groups who may be interested in or affected by your proposal. Early consultation can help avoid or ease opposition to your proposal later in the process.

- Public participation is one of the key principles underlying the RMA. !

- The RMA does not require you, as an applicant, to consult anyone about your application for resource consent, but sometimes there’s a duty under another Act to consult; these duties must still be complied with.

- The RMA does require people applying for resource consent to submit a record of any consultation undertaken and the responses received. This can give decision-makers the information they need to make well-founded decisions.

- There are benefits for an applicant where consultation is concerned.

5. Noise

What is it?

-

Noise is unwanted sound

The environmental and social definitions of noise take account of the effect of the sound rather than its technical nature.

The results of national surveys of typical exposure to noise

show that

- >50% of the population are exposed to day-time noise levels that exceed the World Health Organisation (WHO) ratings for significant community annoyance.

- Other surveys report that around 50% of people find their home in some way unsatisfactory because of noise.

5.1. Noise problems

Unfavourable effects of noise

- Hearing loss - Excessive exposure to noise causes loss of hearing

- Quality of life - Eg: busy roads or airports are considered unpleasant and undesirable as places to live.

- Interference - Disruption of speech or music can be annoying and, in some situations, dangerous.

- Distraction - from a particular task can cause inefficiency and inattention – and may be dangerous.

- Expense - Control of noise is expensive. Businesses can suffer loss of revenue in a noisy environment.

- The construction industry has high levels of noise that can damage workers hearing and health.

- Aim of NZ building regulations for sound insulation: safeguard people from illness or lack of amenity as a result of undue noise transmission.

- On a positive note: room acoustics – good quality sound helps communication - and gives pleasure.

5.2. Hearing Loss

Excessive exposure to noise causes loss of hearing.

The most damaging type affects the Inner Ear – the Cochlea which contains nerve endings that connect to the brain and provide our sense of ‘hearing’.

- Temporary Hearing Loss – (Temporary Threshold Shift) - Ok if you allow 48 hours for recovery

- Permanent Hearing Loss – (Permanent Threshold Shift) from exposure every day. Eg bar staff, construction staff. This loss is permanent.

All hearing losses are added to the continuous hearing loss that accumulates with age – from the time of birth!

Noise factors to measure

1. Energy level - The hearing system reacts to the Sound Pressure Level (SPL) usually measured in decibels (dB)

2. Frequency structure

Some frequencies are more annoying or harmful than others

Eg: high whining frequencies

3. Time Duration

Short periods of noise are less likely to annoy than prolonged exposure

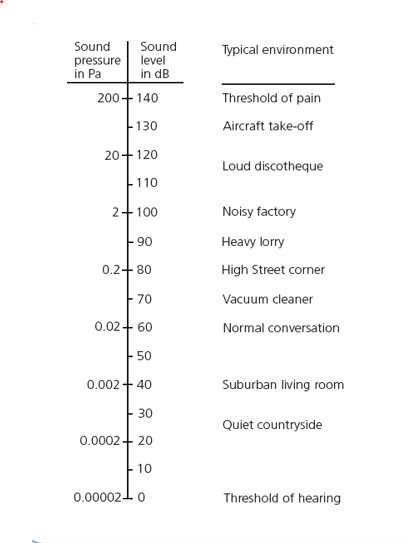

Sound Levels

Decibel (dB) scale used to –

- give a manageable scale of numbers

- match the non-linear response of human hearing

The decibel is a logarithmic ratio of two quantities

- Usually measured in terms of pressure

5.3. Noise Control

Typical sound levels

Changes in sound levels

| Sound Level Change | Effect on Hearing |

| -/+ 1 dB | negligible |

| -/+ 3 dB | just noticeable |

| + 10 dB | twice as loud |

| - 10 dB | half as loud |

| + 20 dB | four times as loud |

| - 20 dB | one-quarter as loud |

Noise Control – Action Areas

1. Source of Sound

Eg from outside the building, or within the building

2. Sound Path

Eg through the air, or through the building structure

3. Receptor/Receiver of Sound

Eg the building itself, a particular room, or a person.

Noise Control - Treatments

When controlling noise it is sensible to work through the action areas in the following order.

1. Source of sound – can it be stopped or reduced in energy.

Eg: changing or treating noisy machinery, noisy people

2. Path of sound – can the noise be reduced during its transmission through the air or a structure

Eg: distance from source, stopping air gaps, increasing sound insulation of structures

3. Receiver of sound - can it be protected

Eg: Insulating a building, or room. Wearing ear defenders

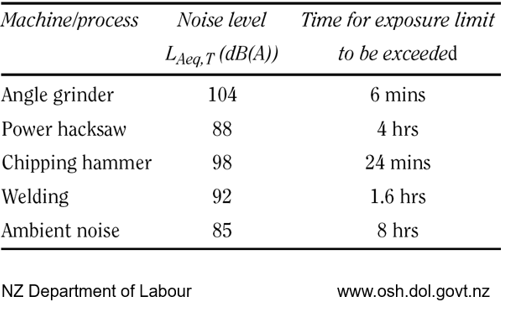

5.4. Hearing Risks from Construction

- The risk of damage to hearing is dependent on the total energy reaching the ear in a given period

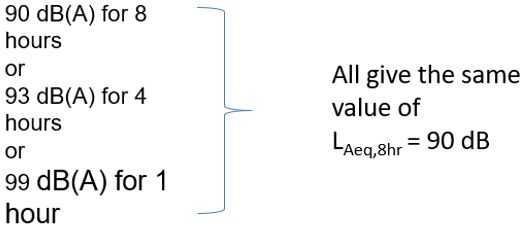

- LA,eq is the basis of safe exposure to noise during an 8 hour working day.

- Current Noise Dose Limit in NZ:

LAeq,8hr = 85 dB

The equivalent continuous sound level compares a varying sound level to a theoretical constant sound which gives an equivalent amount of sound energy.

Equivalent continuous sound level, LAeq,T is that constant sound level which, over the same period of time T, provides the same total sound energy as the varying sound.

Unit: dB(A)

Although human hearing does not judge loudness in terms of energy, the LAeq measurement of accumulated sound energy is found to correlate well to – the annoyance caused by noise and also to damage to hearing.

Energy Equivalents- 3 dB increase corresponds to double the energy.

- By reducing time to half = equivalent ‘dose’ of energy over an 8 hour period.

- Assumptions include a continuous noise output from machinery.

- In situations where noise varies – use integrating sound level meters which sample regularly.

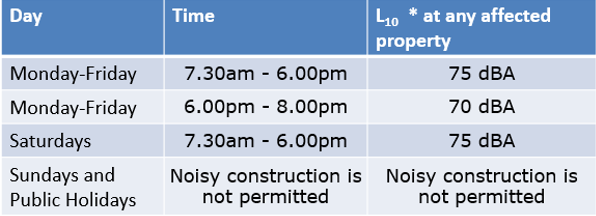

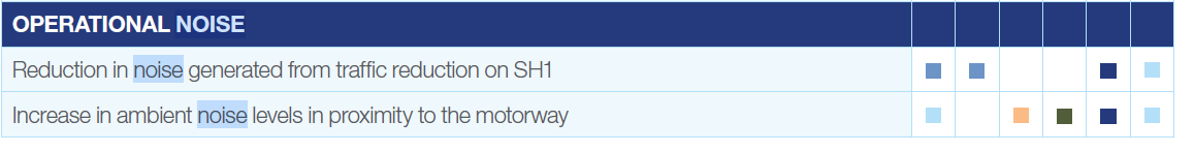

Permissible Noise Levels and Times

Construction work within residential areas:

Where * L10 refers to a noise level which can only be exceeded for 10 percent of the time. E.g. L1075 dBA means that over a 30 minute period, the noise may only go above 75 dBA for three minutes.

5.5. Construction Noise Examples

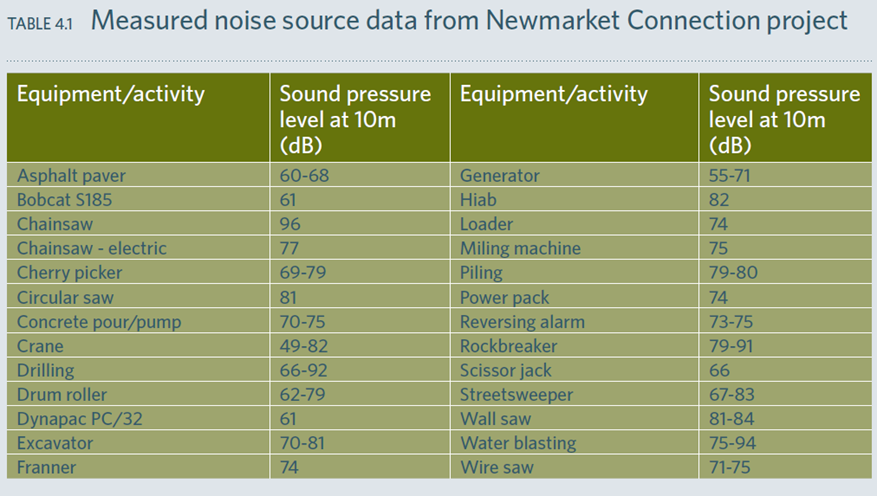

NZ Transport Agency | State highway construction and maintenance noise and vibration guide | SP/M/023 | August 2013 / version 1.0

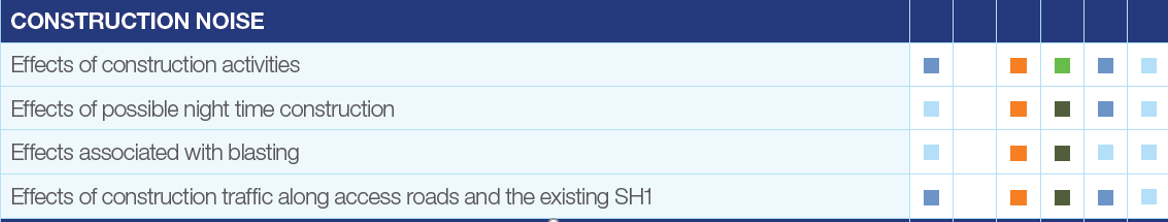

Puhoi to Warkworth - Construction vs. Operational NoiseKey:

Evaluation

Ambient noise

levels in the Project area are relatively low in most locations due to the

absence of major local roads and industry. Noise levels ranged from 40dB LAeq in rural

areas to 73dB LAeq adjacent to SH1. Idenitfy/Quality A Construction Noise Assessment Report

was prepared for the Project, which assesses noise effects relating to the

construction phase of the Project. Operational

noise effects were addressed in AEE Recommended upper limits for

construction noise received in residential zones and dwellings in rural areas:

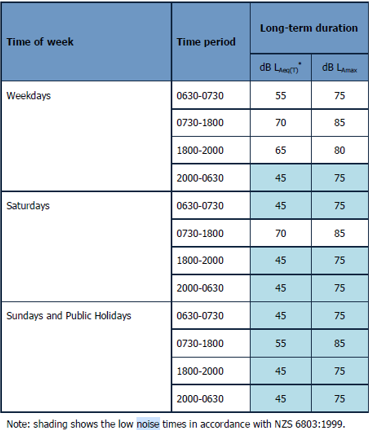

5.6. Assessing Risk

Monitor & Mitigate

On-site measures incl. training of personnel, maintenance of

equipment, noise barriers and enclosures and considerate behaviour and use of

equipment. Off-site measures include public liaison and communication,

temporary barriers, offers of resident relocation and noise level monitoring. Any potential

exceedances of the recommended criteria can be managed and mitigated through a Construction Noise and Vibration Management Plan. Table 15-4: Risk of exceeding daytime noise criteria (70dB LAeq)

5.7. Managing noise through enforcement

Extracted and summarised from Managing Noise Through Enforcement at www.qualityplanning.org.nz [a good resource site]

The primary duty relating to noise under the RMA (Resource Management Act ) is contained in s16. Section 16 of the RMA requires that noise is kept to a reasonable level by adopting the best practicable option. The duty applies to every person who occupies or carries out an activity within New Zealand’s territorial boundaries, including its coastal waters and the airspace above the land and water

District plans and regional plans may set out rules controlling noise, whether at source or receptor.

- Noise controlled at source example: noise being emitted from a factory as measured at the site boundary

- Noise controlled at receptor example: emission controls that require acoustic design of living apartments in commercial centres, to reduce the level of noise to specific levels as received by occupants.

Excessive noise definition

Key features of the definition in s326 of the RMA are:

- It applies only to noise under human control (including that from a musical instrument, electrical appliance, machine, or explosion or vibration).

- It can apply to noise from a person or group or persons (such as people in the outdoor courtyard of a bar).

- The noise has to be of such a nature as to unreasonably interfere with the peace, comfort and convenience of any person (other than the person responsible for it).

- It does not include noise form aircraft in flight (or immediately before or after flight), vehicles driven on roads, or trains (other than when being tested, maintained, loaded/unloaded).

Which procedures?

The difference between the powers and procedures available under the RMA for managing noise should be understood in terms of the outcomes sought, rather than the type or nature of the noise.

|

Nature of noise |

Outcome sought |

Tool |

|

Noise from an on-going activity |

Having operators consider methods that will best ensure reasonable levels are achieved over the long term. |

Section 16 - Best practicable option |

|

Short-term noise |

Immediate cessation or reduction of the noise to a reasonable level. |

Section 327 - Excessive noise direction. This direction will last 72 hours. |

When section 16 is applied the interaction between the operator and the local authority may result in an unopposed.

An abatement notice issued under s322(1)(c) of the RMA is usually the most effective and efficient enforcement procedure for contravention of s16. In practice, however, a local authority should be aware that enforcing the s16 duty may be quite time-consuming.

Identifying and implementing the 'best practicable option' may take months to implement because of the requirements of design, sourcing new equipment and skills, testing the solution, and building it. Alternatively, relocating the activity to an environment where the noise will have less impact may also take considerable time.

5.8. Useful inks for noise control

Please follow these links fro more information on noise control.

|

http://www.nzta.govt.nz/resources/sh-construction-maintenance-noise/ NZTA – State Highway Construction and Maintenance Noise and Vibration Guide |

|

RMA resource website |

|

http://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/EN/environmentwaste/stormwater/Documents/bmpnoise201203.pdf Auckland Council - general guide |

6. Consultation Principles

A number of principles that help define the meaning of good consultation have emerged from case law under the RMA:

A number of principles that help define the meaning of good consultation have emerged from case law under the RMA:- Early – consult as soon as possible when the details of your proposal are less ‘set in concrete’ and you have more flexibility to make changes to address issues raised by interested and affected persons.

- Transparent – be open about what you want to achieve, what scope you may have to change certain aspects of your proposal, and why there might be elements that you may not be able to change.

- Open mind – keep your views open to people’s responses and to the benefits that might arise from consultation.

In addition to these, it is worth noting that the following points will help your consultation process:

- Two-way process – consultation is intended as an exchange of information and requires both you and those consulted to put forward their points of view, and to listen to and consider other perspectives.

- Not a means to an end – while consultation is not an open-ended, never-ending process, it should not be seen merely as an item on a list of things to do that should be crossed off as soon as possible.

- Ongoing – it may be that consultation, or at least ongoing communication, will continue after your application has been lodged or even after a decision has been made.

- Agreement not necessary – consultation does not mean that all parties have to agree to a proposal, although it is expected that all parties will make a genuine effort. While agreement may not be reached on all issues, points of difference will become clearer or more specific.

The benefits of consultation include:

- Improving outcomes

- Gaining local knowledge – consultation may reveal information on a range of issues (including things such as local traffic or flooding conditions) that is important to your proposal but that you might not otherwise be aware of.

- Incorporating tāngata whenua values and interests there may be matters of significance to Māori, such as traditional burial sites, that can be accommodated into your proposal.

- Enhanced proposals and improved environmental outcomes – consultation may provide input that will improve your project or idea and reduce its impact on the natural, physical, cultural and social environment.

- Making the consent process easier – consultation may lessen any concern, doubt or confusion people may have about your proposal (in the absence of accurate information). This can reduce potential opposition, and improve the chances of consent being non-notified and granted.

Tāngata whenua

This is an extremely important part of the consultation process in New Zealand for the following reasons:

- Benefit by understanding the Māori world view – tāngata whenua (iwi, hapū, whānau) have a long-standing association with the natural environment. Understanding these cultural values and interests can result in improved proposals.

- Unique to New Zealand and our national identity – tāngata whenua participation in the resource consent process can foster kaitiakitanga (the exercise of guardianship expressed in part through an ethic of stewardship) and other Māori concepts that are unique to our country. These may be used to enhance your proposal.

- Helping council assess RMA obligations – ensure the council can see how your proposal has addressed RMA requirements relating to Māori and the Treaty of Waitangi, and strengthen relationships.

6.1. Who & how do I consult?

Before you do any consultation, you need to think about the nature, extent and size of potential effects. What kind of effects will your proposed activity create – visual effects, traffic, noise, dust? How far will they extend – to adjoining properties, to the whole neighbourhood, to a stream catchment? How large are those effects in the context of the environment – minor, moderate, significant? Those who may be consulted include:

Before you do any consultation, you need to think about the nature, extent and size of potential effects. What kind of effects will your proposed activity create – visual effects, traffic, noise, dust? How far will they extend – to adjoining properties, to the whole neighbourhood, to a stream catchment? How large are those effects in the context of the environment – minor, moderate, significant? Those who may be consulted include:

- owners, occupiers and users of adjacent and nearby land

- downstream water users

- users of the same groundwater resource

- occupiers of land living down-wind of a proposed discharge to air

- people or groups with a specific interest in the site or area (such as guardians of an estuary)

- tāngata whenua (iwi, hapū, whānau)

- statutory, infrastructure and utility organisations (such as government departments, councils, and roading and rail authorities).

How do I consult?

Where do I start?

Discuss the proposal with the council who may be able to help you list the parties to consult.

Prepare consultation material such as:

- a brief written description and plans of your idea/proposal

- a tentative assessment of environmental effects

- measures you would propose to reduce the extent or impact of those effects.

Consult with identified persons and groups:

- by letter (usually) in the first instance with an offer of follow-up contact to discuss the proposal in the following days

- by telephone (where possible) to confirm that they’ve received the information you sent, and to arrange further communication (preferably face-to-face) to determine any issues

- at an on-site meeting, where you explain your proposal.

6.2. Case Study

Central Plains Water Enhancement Scheme

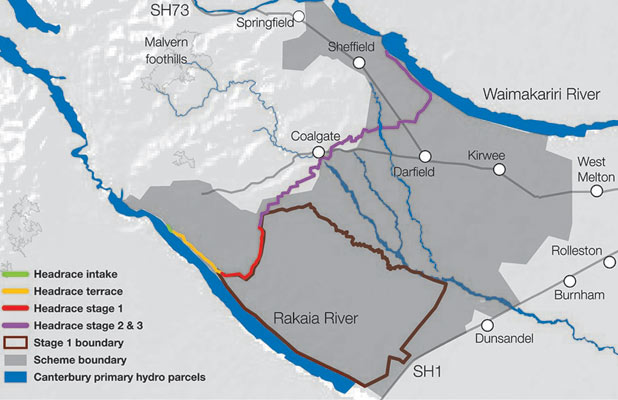

- The Scheme lies between the Southern Alps to the west, and SH1 and the Waimakariri and Rakaia Rivers, lying entirely within the Selwyn District Council District. The irrigation scheme has been designed for 60,000Ha, with potential to irrigate up to 80,000Ha if more water is available.

- With a current estimated construction cost of $345 million (excluding on farm costs), the consented CPW Scheme will be one of the largest construction projects ever undertaken in the South Island.

- The Scheme will utilise run of river water from both the Rakaia and Waimakariri Rivers. The Rivers will be linked with a 56km headrace canal running around the foothills and will channel water probably via a piped gravity distribution system through 500km of reticulation. Water within the canal will be about 4m deep and 20 – 25m wide at the surface. Irrigable land above the canal can be watered via pumped systems.

Social Impact Assessment

- Description of the social environment

- Planning phase impacts

- Construction effects

- The effects of scheme operation

- Social effects of land-use change under irrigation

- Recreation effects

- Mitigation and management of effects

- Recommendations for mitigating and managing change

- Community liaison and social impacts management

- Actions on scheme construction issues

- Actions on scheme operation issues

- Recreation impacts management

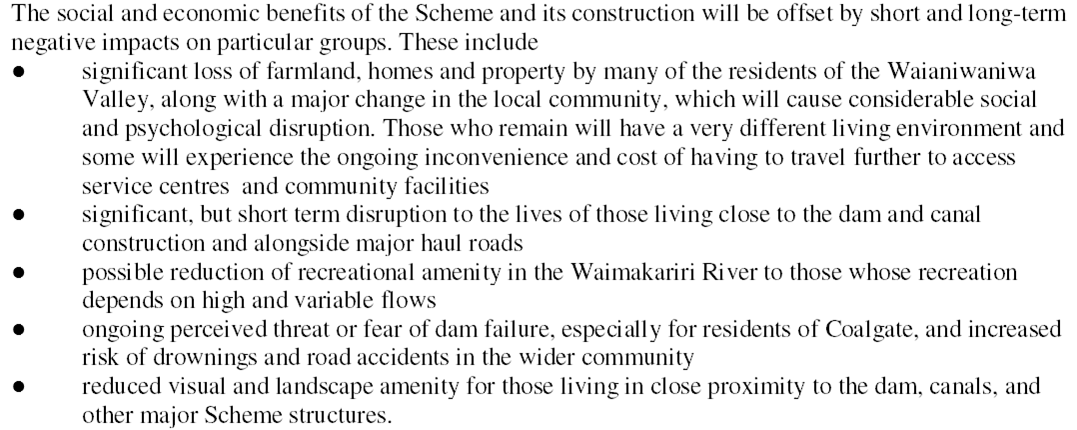

The social impact assessment of this scheme identified the potential positive and negative social effects for people and communities during construction and operation, including possible mitigation (or enhancement) measures.

Specific objectives of the assessment were to:

- assess the nature, likelihood and significance of social effects on people and communities

- recommend appropriate monitoring/mitigation/enhancement measures where significant effects are identified

- prepare a comprehensive and technically robust social assessment that will provide appropriate evidence on social impacts for consent hearings, and any other recommendations.

6.3. Example: Social Assessment

The social assessment for the central plains irrigation project covered the following social effects:

The social assessment for the central plains irrigation project covered the following social effects:

- water takes from the Waimakariri and Rakaia river systems

- an impoundment structure and reservoir flooding a large part of the Waianiwaniwa Valley canals and other headwork structures taking water from the two rivers and distributing it to up to 60,000 ha of farm land

- intensification of land use on farm land previously not irrigated by ground water (around 30,000 ha)

- downstream changes to watertables, water quality and waterways

- a construction phase of three years requiring a workforce of up to 200 people.

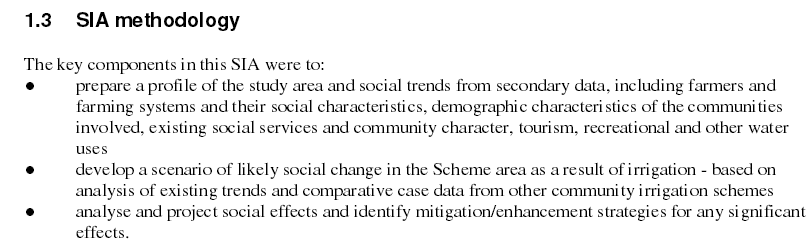

The SIA methodology is shown below along with the conclusions of the assessment:

As management of the social impacts was required, prior to the construction commencing, CPW needed to establish a scheme Community Liaison Committee. This included:

- Community representatives from among the residents of Hororata, Coalgate/Glentunnel, the Waianiwaniwa Valley, Sheffield, and Darfield

- a community/economic development officer from the Selwyn District Council

- recreational representatives

- scheme shareholder representatives

- a CPW community liaison officer.

6.4. Summary

The previous pages have demonstrated that:

The previous pages have demonstrated that:

- People of NZ are diverse in culture, race and lifestyle

- Effects on people are various and complex

- All of mans activities affect ‘man’

- Some of the tools require a fundamental understanding social fabric

- Assessment of impacts is not always straight forward and involved experts

- How those affected are taken into account key

Effective consultation is crucial so make sure you take the time to:

- listen to what others have to say and consider the responses

- allow sufficient time for consultation

- make a genuine effort to consult

- conduct the process in mutual good faith

- provide enough information to enable the party being consulted to make intelligent and useful responses

- keep an open mind and be ready to change the proposal or even hold meetings, provide relevant and further information on request

- wait until those being consulted have had a say before making a decision

- re-open the consultation process if necessary